Last week I introduced you to the genus Lithops, which have a fairly unusual anatomy. While observing my own lithops plants over the last several weeks, I made a few more miscellaneous observations that I wanted to share with you. I hope you find them diverting!

Otherwise – happy holidays! I look forward to providing more content to you, the reader, in the coming year.

Splitting!

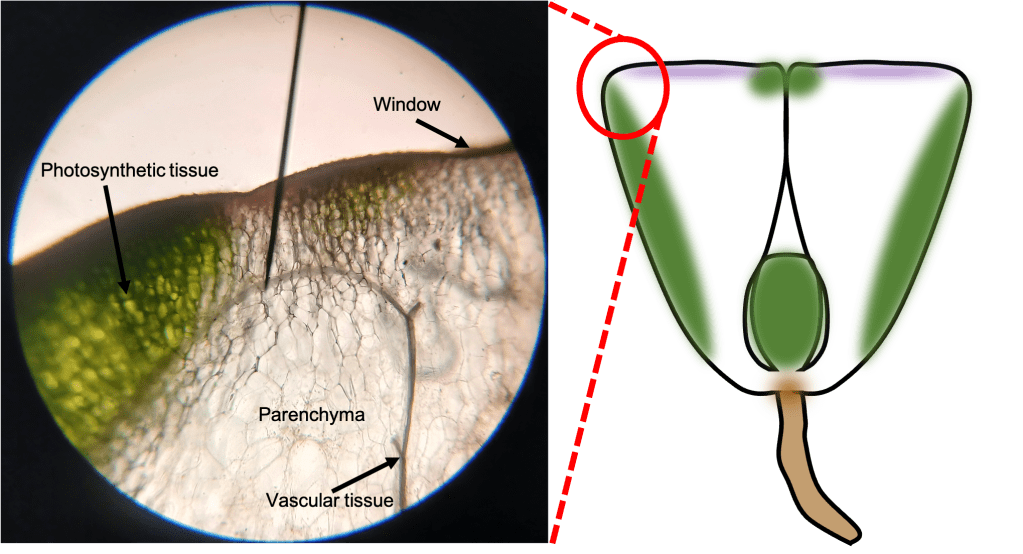

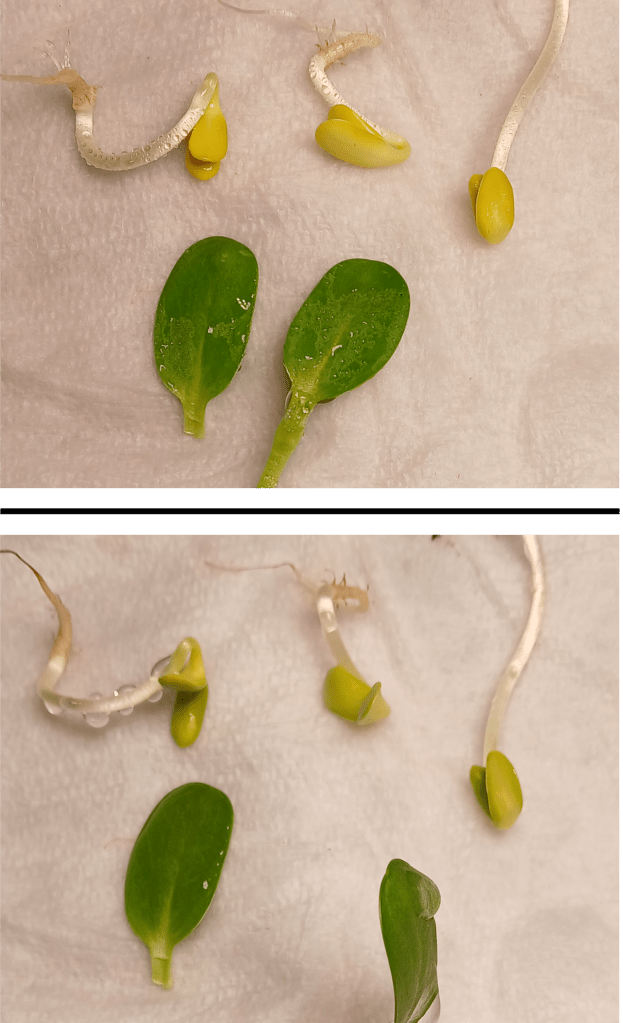

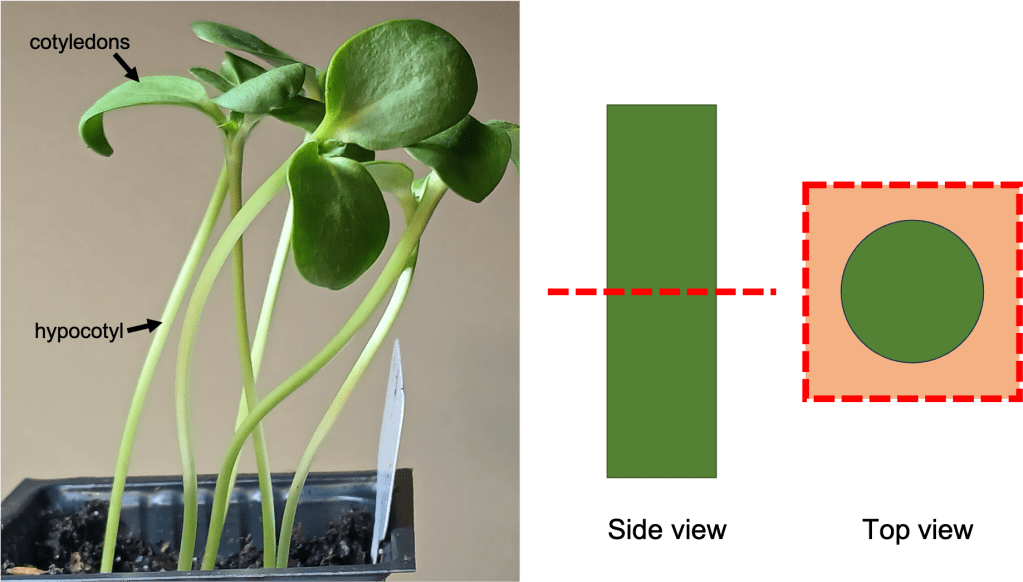

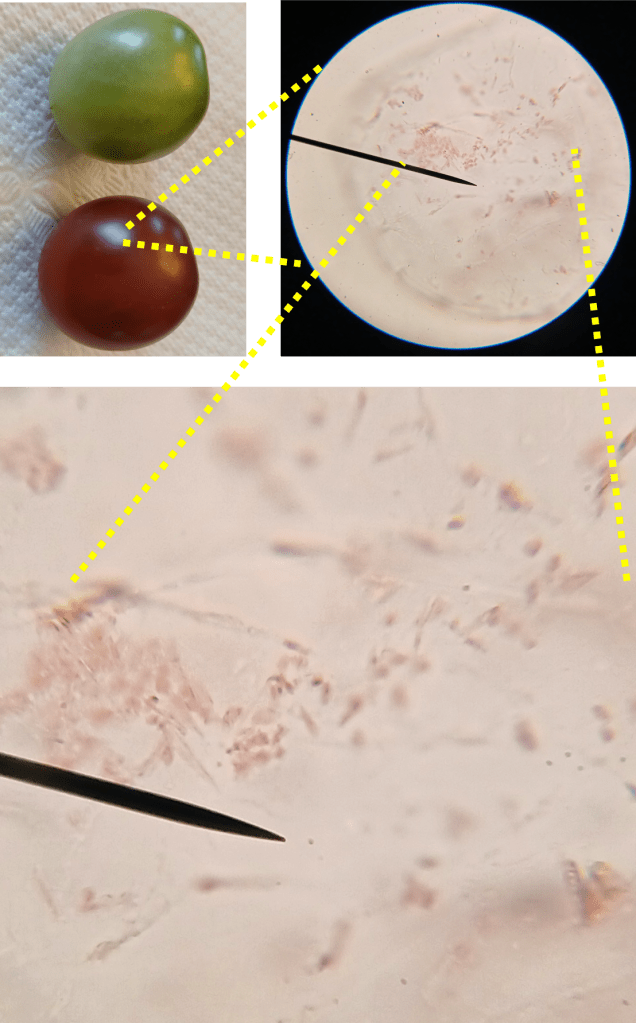

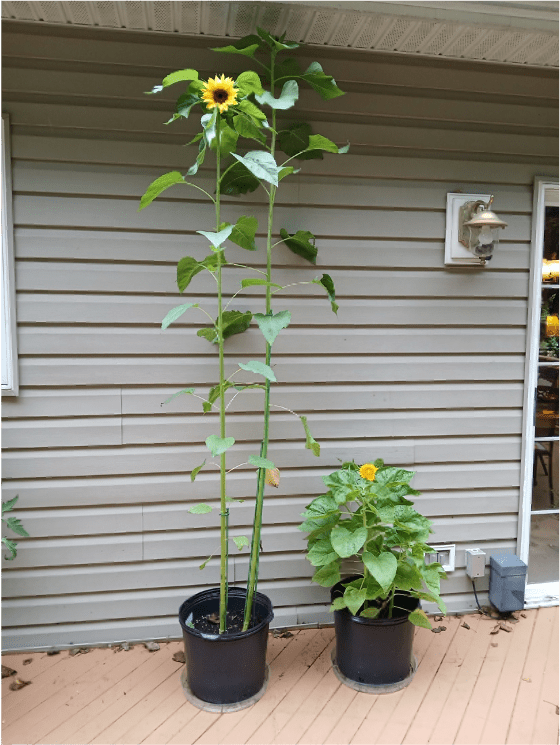

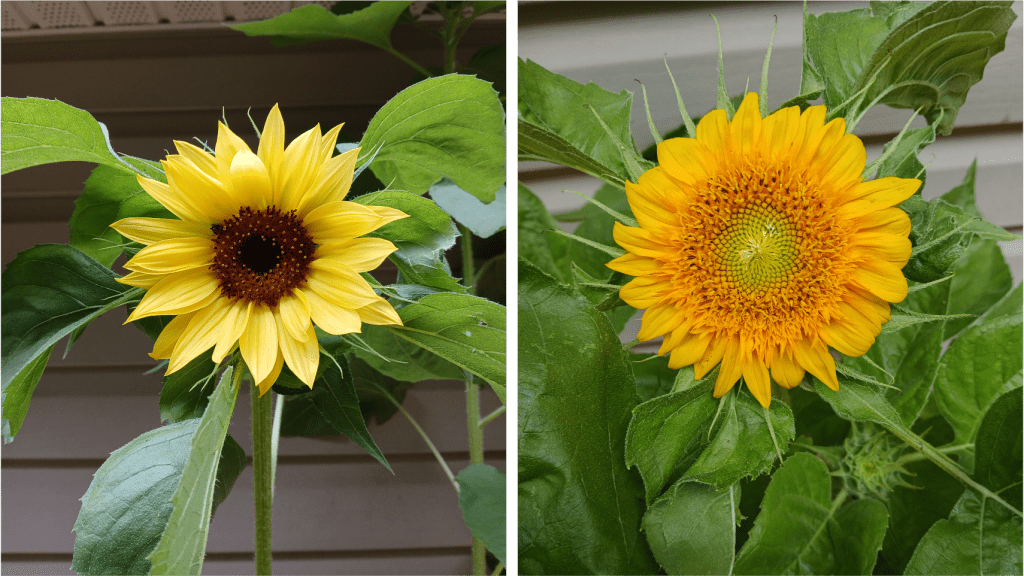

OK, this observation was particularly exciting for me, a first-time lithops owner. I noticed that one of my plants has started splitting! This is the process by which lithops grow. It looks like this:

Figure 1. A splitting lithops plant!

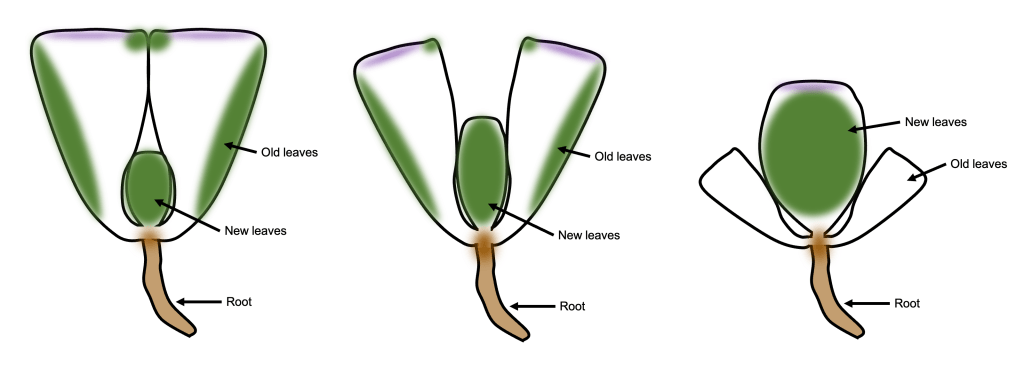

What are we looking at here? As we learned last week, when you look at a lithops plant, you can see two fused succulent leaves. New sets of leaves form deep inside the center of the plant, and are not initially visible (See Figure 2 left). As the new leaves grow, they push the old leaves apart. To conserve water, the new leaves will absorb water from the old leaves; this is a helpful adaptation to living in dry climates [4]! Eventually, the old leaves shrivel and die, leaving just the new pair of leaves behind.

Figure 2. Simplified diagram of the splitting process.

Itchy scratchy…

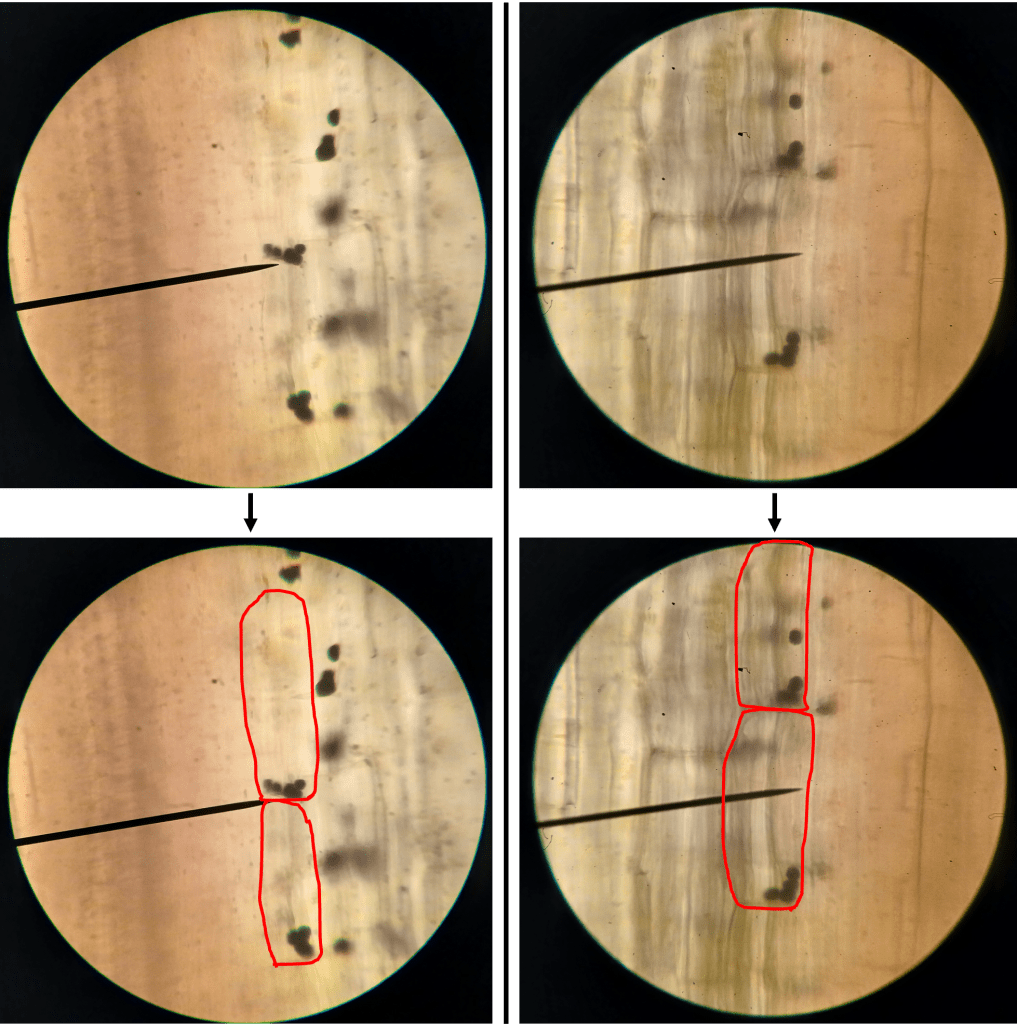

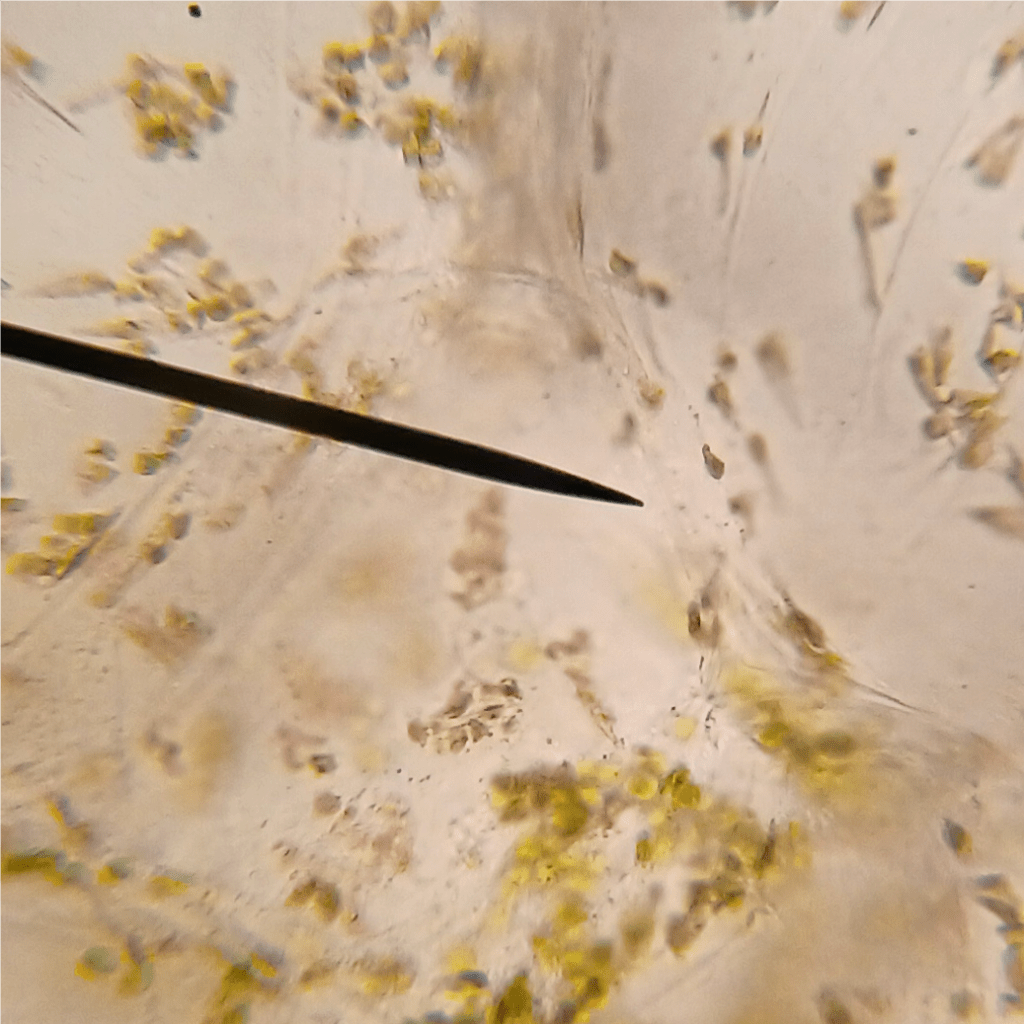

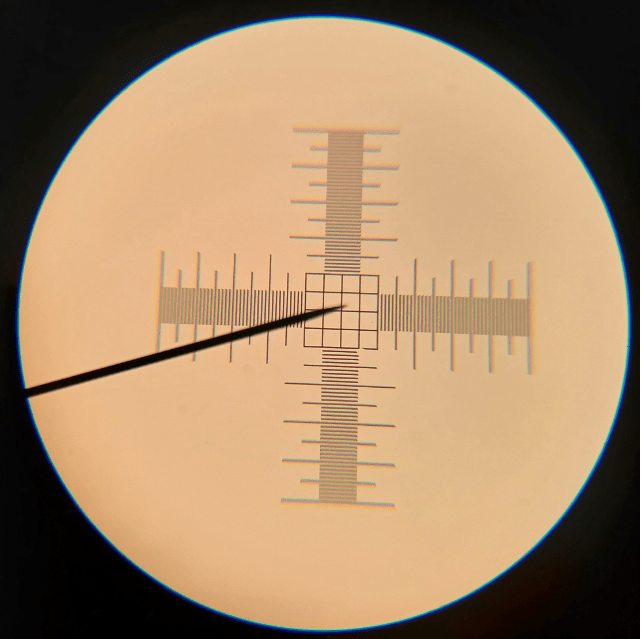

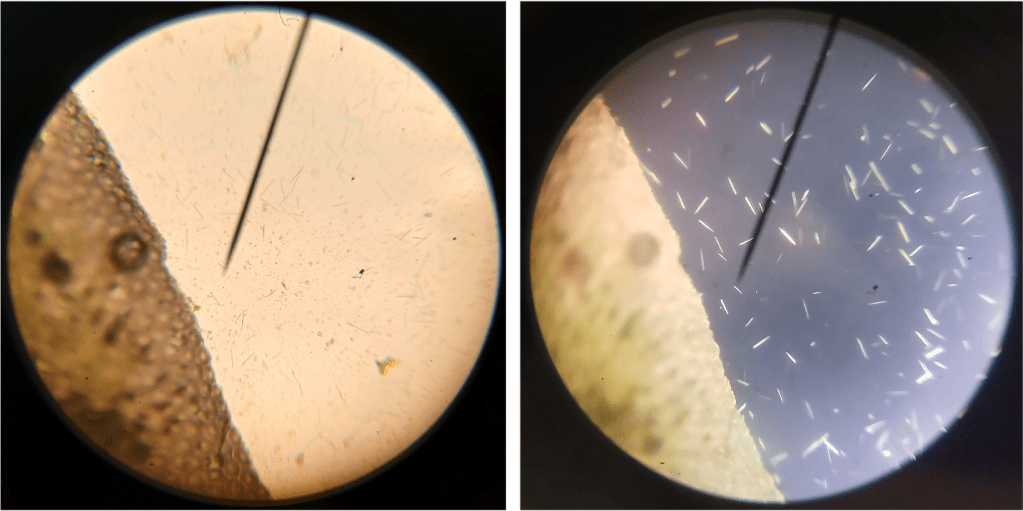

One of the things I noticed while looking at lithops tissue on the microscope was the presence of lots of tiny crystals. These were particularly abundant when I squished the tissue (which releases cell contents into the water that the tissue is suspended in). These crystals are very difficult to see under normal illumination (Figure 3 left). However, using polarized light microscopy, their presence becomes… crystal clear (Figure 3 right)!

(For the polarized light microscopy, I ordered a cheap polarizing filter sheet online and cut it into two halves. I placed one half beneath my sample, and the other half above it. Then, I rotated the top polarizer so that it was perpendicular to the bottom polarizer. This is super easy to do at home! I won’t say much more here, but there is a really excellent animation explaining the principle behind polarized light microscopy on the relevant Wikipedia article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polarized_light_microscopy).

Figure 3. Raphides from damaged lithops tissue. Left: Under normal illumination. Right: Using polarized light microscopy.

From my reading, I am reasonably confident that we are looking at raphides here. Raphides are tiny crystals (typically calcium oxalate) which are common in many species of plants. They are thought to protect plants against predation, as they are sharp and could in theory cause irritation in animal tissues that come in contact with them.

I found this interesting study [2] which demonstrates that raphides inhibit the growth of silkmoth larvae when ingested, particularly in combination with cysteine protease, an enzyme common in plant tissues. Importantly, this study verified that the shape of the raphides, rather than their chemical composition, contributes to their defensive function (since amorphous calcium oxalate particles did not have the same effect) [2]. Fascinating. There is apparently also evidence that raphides in large quantities are toxic to humans. This article about an outbreak of foodborne illness in Chicago associated with raphide consumption made for particularly grim reading [6].

I couldn’t find much information about raphides in lithops specifically, although the thesis of Robert Wallace (Rutgers University, 1988) does note their presence [5]. So, someone has seen this before! Whew.

AAAAAAAAAAAAH

Stomata are pores found on virtually all plants which facilitate gas exchange with the environment. Plants take up oxygen from the atmosphere for respiration and CO2 for photosynthesis. Conversely, oxygen is also released from plant tissues as a byproduct of photosynthesis, and CO2 is released as a byproduct of respiration. Thus, stomata help plants to achieve the correct concentration of oxygen and CO2 in their tissues. Stomata also allow plants to transpire (release water via evaporation), which is essential for thermoregulation and for water transport. I might do a dedicated post (or a few!) about stomata later – they’re really interesting!

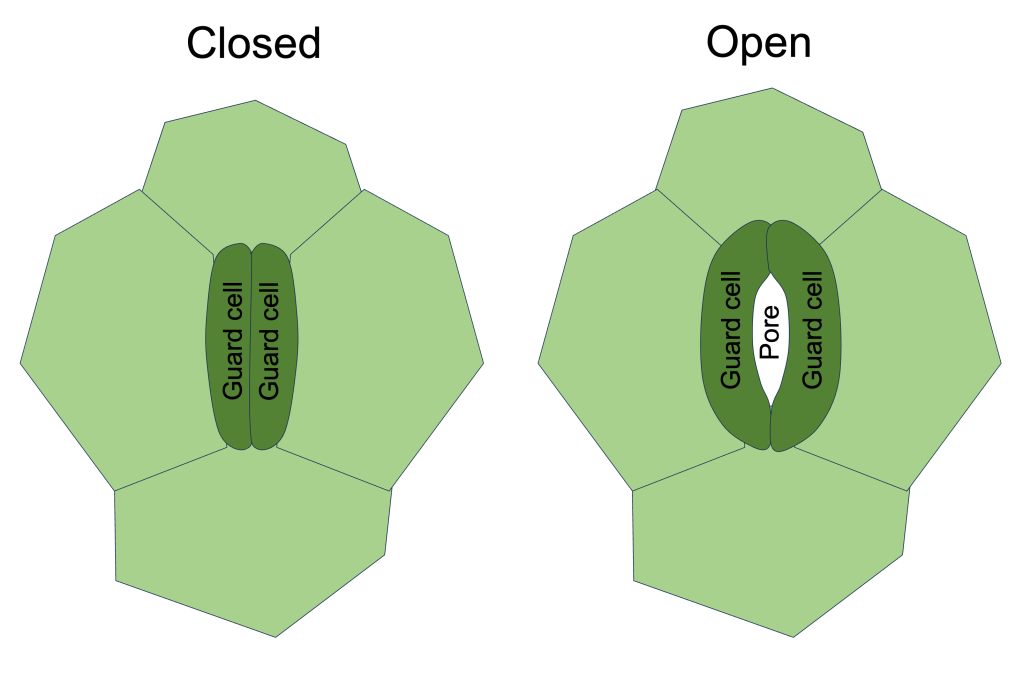

Plants control gas exchange by opening and closing their stomata. This opening/closing is facilitated by specialized cells known as guard cells. Two guard cells lie on either side of every stomatal pore. The pore opens when the guard cells inflate, and closes when the guard cells deflate (See Figure 4). Guard cells inflate/deflate due to intake/expulsion of water via osmosis. How this is controlled is beyond the scope of this post, but I may come back to this at a later date.

Figure 4. Simplified diagram of a single stoma in the closed state (left) and open state (right).

Why am I talking about stomata now? I am talking about stomata because I came across this interesting blog post [3] a short while ago. It’s a great piece on lithops biology (would recommend!), but one sentence stood out to me: they claim that one species, Lithops dorotheae, has 3 guard cells per stoma instead of the usual 2! This was surprising to me, and raised a few questions:

- Guard cell configuration is highly conserved amongst different groups of plants. Why should L. dorotheae be different?

- How would the stomata be able to open/close with 3 guard cells?

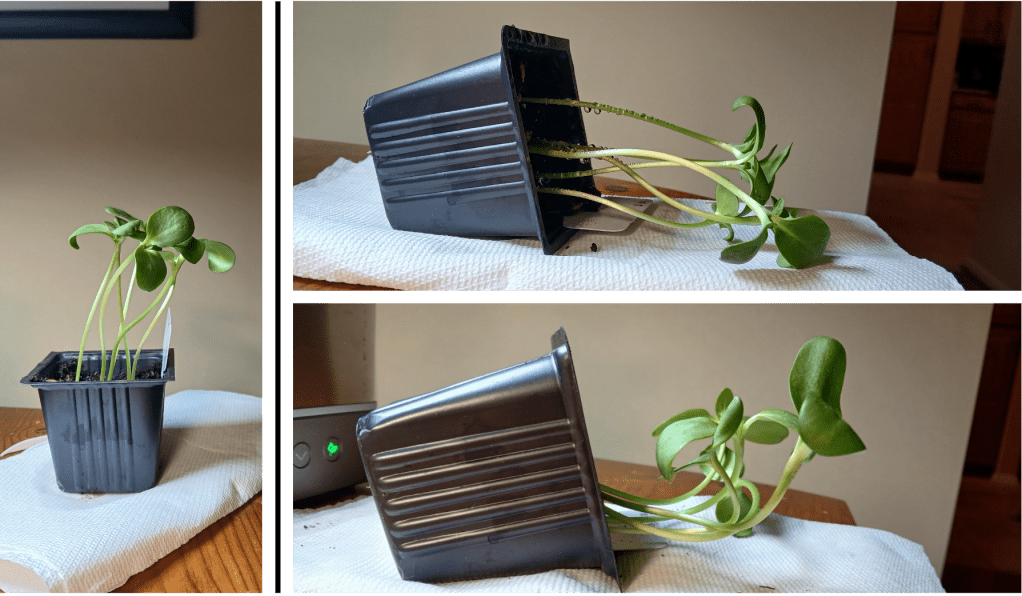

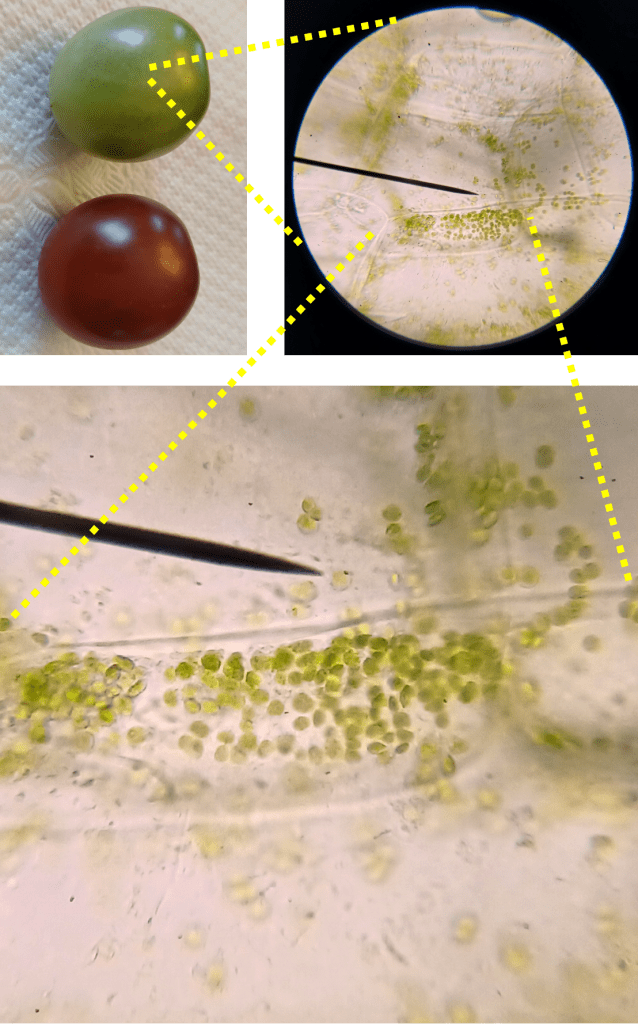

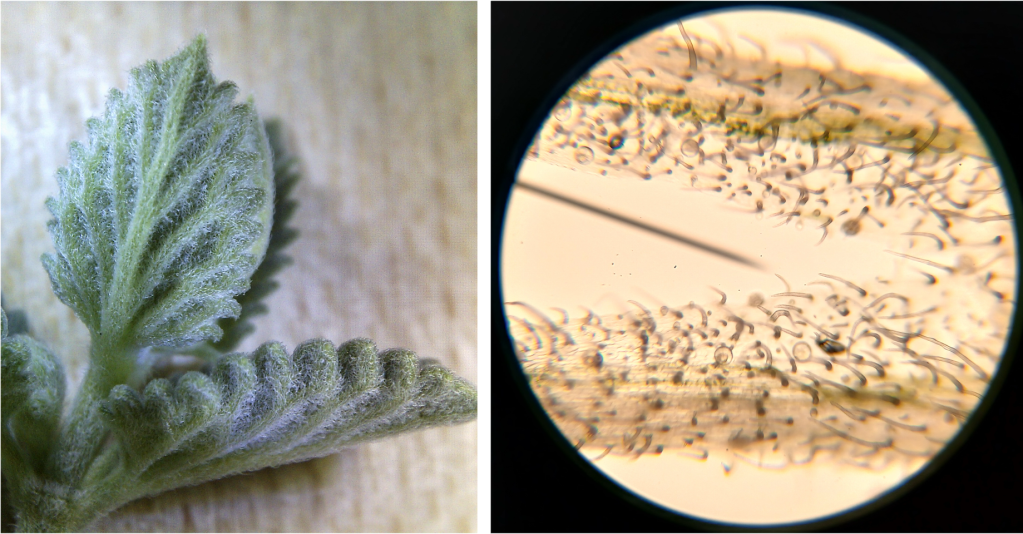

I decided that it would be fun/worthwhile to verify this myself. To this end, I did two things: First, I tried to find the original source of this information to see what it said, exactly. Second, I acquired some domestically-grown L. dorotheae plants so that I could make my own observations! Note: when purchasing lithops, it is important that you buy domestically-grown plants, for ecological, health, and legal reasons. Always check the source. Anyway…

Figure 5. A small L. dorotheae plant. It looks a bit different to my other lithops (which I’m pretty sure are L. karasmontana). Check out the little red stripes!

OK, so the source of the information about the unusual guard cells in L. dorotheae appears to be that Wallace thesis from 1988 [5]. However, Wallace says that that stomata in L. dorotheae have 3 subsidiary cells… NOT that they have 3 guard cells. Aha! This makes more sense.

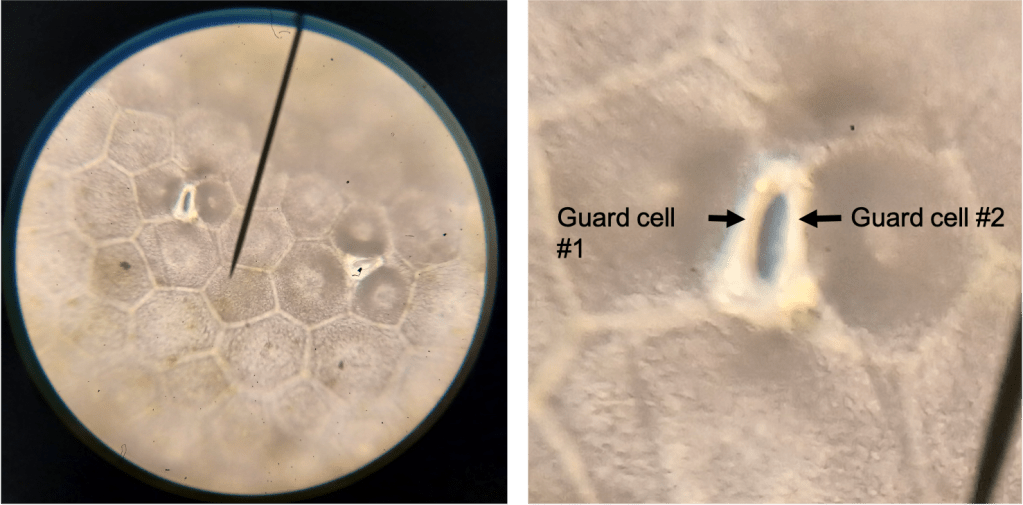

Subsidiary cells are specialized epidermal cells which surround the pair of stomatal guard cells. In the case of my L. karasmontana plant, these cells are indistinguishable from other epidermal cells (Figure 6 left). However, in L. dorotheae, I observed the presence of 3 or 4 cells surrounding each stoma, which are more darkly colored than the other epidermal cells (Figure 6 right). I think this is probably what Wallace was referring to. Importantly, the stomata on my L. dorotheae plant have the normal 2 guard cells… (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Epidermis of my L. karasmontana (?) plant (left) and L. dorotheae plant (right) at 100X magnification. The top half of the figure are the original images; In the bottom half, I have circled the stomata that I can see.

Figure 7. Stomata in L. dorotheae, at 400X magnification. Left is the original image; Right is a cropped version of the same image blown up to show a single stoma clearly. The two guard cells are visible (compare to my drawing in Figure 4).

What do the subsidiary cells actually… do? Unfortunately, this is not an easy question to answer, and probably depends on the species of plant. One thing that Wallace (1988) mentions is that stomata in lithops are sunken below the main surface of the epidermis [5]. The shape of the subsidiary cells may help to achieve this sunken topography. It has been theorized that sunken stomata are an adaptation to prevent excessive water loss in plants growing in dry climates [1]. Having sunken stomata increases the depth of the boundary layer of air above the pore, which may slow the diffusion of water molecules away from the pore [1].

Works cited:

[1] Gray, A., Liu, L., & Facette, M. (2020). Flanking support: How subsidiary cells contribute to stomatal form and function. Frontiers in Plant Science 11. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00881

[2] Konno, K., Inoue, T.A., & Nakamura, M. (2014). Synergistic Defensive Function of Raphides and Protease through the Needle Effect. PLoS One 9(3), e91341.

[3] Living stones: Growing Lithops. (2018, October 25). Nerd Rambling. Retreived December 21, 2025, at: https://atreyuoz.blogspot.com/2018/10/growing-lithops.html.

[4] Sajeva, M., & Oddo, E. (2007). Water Potential Gradients beween Old and Developing Leaves in Lithops (Aizoaceae). Functional Plant Science and Biotechnology, 1(2), 366-368.

[5] Wallace, R. (1988). Biosystematic Investigation of the Genus Lithops N.E.BR. (Mesembryanthemaceae). PhD dissertation, Rutgers University.

[6] Watson, J.T., Jones, R.C., Siston, A.M., Diaz, P.S., Gerber, S.I., Crow, J.B., & Satzger, R.D. (2005). Outbreak of food-borne illness associated with plant material containing raphides. Clinical toxicology 43(1), 17-21.